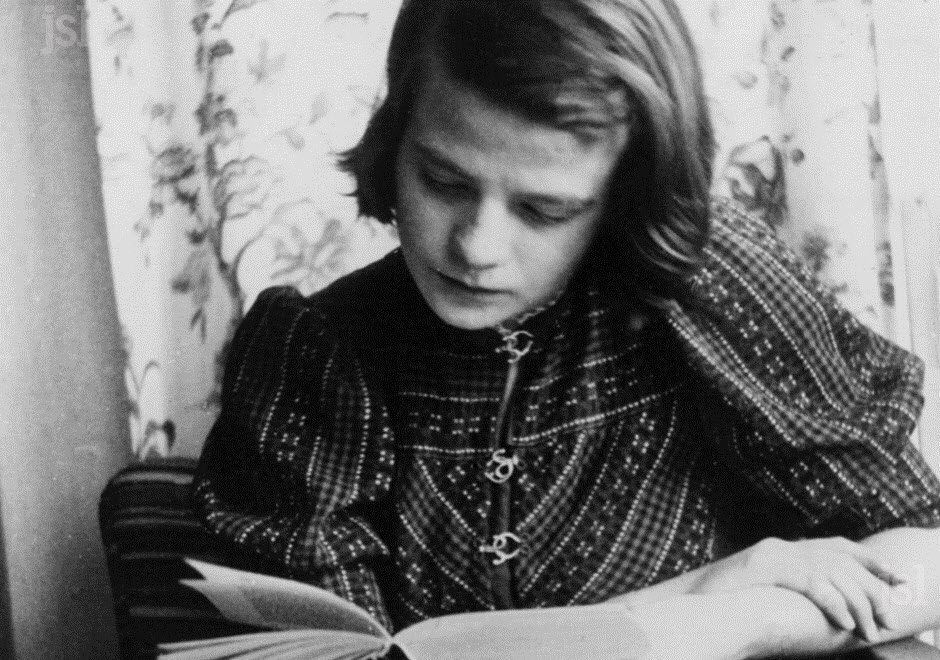

Sophie Scholl, a faithful young woman against Hitler

Sophie Scholl would have turned 100 years old this spring. She has not aged more than 21 years. She was executed after openly resisting Hitler and the Nazis. “Her faith was decisive for her resistance.”

German Protestant pastor Robert M. Zoske (68) led a special commemoration service in Hamburg on a Sunday early May, broadcasted over the radio by Norddeutscher Rundfunk. “The theme of the service was Sophie 100,” the pastor says in a Teams interview.

That the broadcaster’s choice fell on Zoske to preside over the service should come as no surprise. In 2014, the pastor obtained his doctorate on Hans Scholl, Sophie’s brother, one of the initiators of the Christian resistance group Weisse Rose (white rose). A few months ago, he published a book about Sophie.

What is your affinity with Hans and Sophie Scholl?

“In 2010, I met Barbara Beuys in Antwerp, who wrote an impressive biography of Sophie Scholl shortly before that. Since my youth, I have been interested in National Socialism and the resistance movement in Germany. But this book particularly I found fascinating.

Barbara Beuys recommended the Institut für Zeitgeschichte in Munich to Zoske. There you can find the archive of Inge Aicher-Scholl, Hans’ and Sophie’s sister, who died in 1998. The pastor was lucky that his mother-in-law lived in Munich. “The next time my wife Beatrix and I visited her, I stopped by the institute,” he said.

What did you find?

“Almost 800 books on microfilm, including poems by Hans, but also letters and diaries by him and his sister Sophie. It was difficult material to access because much of it was written in the so-called Sütterlin script. This old German script is difficult to read. I copied and transcribed everything by hand. That material formed the basis for my dissertation.”

In 2014, Zoske put the finishing touches to his dissertation. A few years later, in 2018, on the 100th anniversary of Hans’s birth, he released it abridged and rewritten for a wider audience. “Yes, and if you make a portrait of Hans, you should also make one of Sophie. So that’s what happened now.”

To what extent does your biography differ from that of Barbara Beuys? She has also seen and used the same archive.

“In each of the eleven chapters in the book, I have used new source material that Beuys did not know or hardly used. The main difference is that I focus on her Christian faith and say very explicitly: Her faith was decisive for her resistance.”

How would you describe Sophie?

“She was a sensitive, religious young woman who wanted to do something. “Wanted” is actually too weak. She knew that she could not bring down Hitler herself, but she had to show herself that there was another Germany. In her conscience, she was bound.”

Did her parents precede her in this?

“Robert Scholl, her father, was a pacifist. In the First World War, he refused to shoot a gun. That’s why he joined the medical troops. Sophie’s father believed that if Jesus were on earth today, He would preach non-violence.

In this, he was diametrically opposed to Roman Catholic and Protestant preachers who said: “We must fight for God and fatherland.” At the same time, he was more of a cultural Protestant. He went to church because of his work as mayor.”

What about his wife?

“His wife Magdalena was a joyful pietist. The remarkable thing was that she was ten years older than her husband. She was a deaconess and assumed that she would remain unmarried, live in simplicity and put her life at the service of her neighbour. Then she met Robert and fell in love with him. She gave up her vocation and devoted herself entirely to her family.

In her life, she trusted God completely. She believed: everything comes from God’s hand; I can accept that, and it is good for me. She tried to pass this on to her children. Without this faith, her children would never have joined the resistance. Faith was the foundation that gave them strength.”

How did father and mother Scholl look at the Nazis?

“The parents of Hans and Sophie swam against the tide. They were critical of the National Socialists from the very beginning. They have never been worshippers of Hitler.

Did that make them an exception as Christians?

“You can definitely say that. Just look at the churches and then the pastors. Many church leaders saw Hitler as the Führer sent by God. Only a few people didn’t like Hitler at all.”

In your book, you write that Sophie was not opposed to Hitler from the start.

“Her opposition to Hitler grew little by little. There was no Damascus experience: a turn at a specific moment. Until 1941, Sophie was a member of the Bund Deutscher Mädel. She still called on others to join. She wrote to a friend: “You should do the same because it is the right thing to do.”

In the biography written by her sister Inge in 1952, one can read that Sophie distanced herself from the Hitler-Jugend already before the war. Zoske disputes this. When her brother Hans was locked up for a short time at the end of 1937 because of a homosexual relationship, Sophie cautiously began to doubt the Nazis. But even in 1941, she did not say that Hitler had to leave. Gradually she began to question the regime and distance herself from it.

More things that Inge wrote about her sister Sophie turned out to be false, Zoske discovered. “Inge stated that Sophie was already special in her childhood. From early on, everything supposedly pointed in the direction of that last great act of resistance. She wanted to turn Sophie into some kind of saint. To really get to know Sophie, you have to throw out everything that has been written before and the films that have been made.”

In the same way, Sophie does not appear to have done much for a Jewish classmate, as Inge writes. Zoske: “I have had correspondence with the daughter of this classmate. She said that her mother had always said she had no contact with Sophie because she was an enthusiastic Nazi. They were not friends with each other.”

Indirect evidence comes from two letters Sophie wrote a day after Kristallnacht from November 9th till 10th 1938. “The family was living in Ulm at the time, and the city was in a sorry state. Sophie talks extensively about what she experienced in the letters, but she does not mention this pogrom night. And the mail was not checked then so that she could write freely. If it had affected her, she would have spoken about it in one or two sentences. Apparently, it didn’t move her.”

Still, she comes to that grand act.

“Absolutely. She has been on the wrong path for years. However, she has repented. Jesus says in the Bible: repent and believe the Gospel. That is what she did. In 1942 she wrote to a friend: “Have I been dreaming all this time? Perhaps. I believe I have been awakened.”

Adults looked up to Hitler as a saviour. Why should a 13- or 14-year-old girl be any wiser? She had to be older and experience things to come to a different understanding.”

She also read a lot, from Thomas Mann to Augustine.

“Sophie read an awful lot. At the end of her life, this was also a kind of anti-attitude. When she had to do her labour service, she isolated herself with her books from the other girls who were not interested. And then she read Augustine or “The Magic Mountain” by Thomas Mann or the Bible.”

In her letters, she often struggled with faith.

“That went deep and was very special for such a young girl. She knows her doubts of faith but holds on to God. In this, she is typically Protestant. She once wrote, “When I pray, sometimes I don’t know to whom I should pray. Sometimes praying is difficult, but then only praying helps.”

There are stories that Sophie became a Roman Catholic at the end of her life. Are those stories true?

“No, it was Inge who gave birth to this fairy tale because she herself had switched to the Roman Catholic Church in 1945 and had even been baptised again. She would have liked this to happen to Hans and Sophie as well. Later she stated that if Hans and Sophie had lived longer, they would have converted to the Roman Catholic Church.

According to Werner, the other brother of Hans and Sophie, the non-denominational Christoph Probst joined the Roman Catholic Church in prison. When mass was served for him, Hans and Sophie said they wanted to celebrate Holy Communion with their fellow combatant. The priest then said that they would have to convert because an ecumenical Holy Communion was forbidden. Hans and Sophie did not want this and were then given bread and wine by a prison chaplain.

Sophie’s last conversation with her mother is very impressive.

“It is indeed very moving. Magdalena was allowed to visit Sophie in prison just before her execution. At the farewell, she says: “Aber gelt, Jesus.” That means: hold on to Jesus! Or: keep your eye on Jesus! Then Sophie looks at her mother in agreement and says: “But you too, mother.” She confirmed her mother’s pious pietistic faith. And she made it clear to her mother that she too can believe and do something against the regime. That is where faith and works come together. And in all doubt, Jesus is her only hope and anchor.”

How did the family fare?

“The death of their children marked their life. Later, their son Werner was killed on the Eastern Front. There are letters from mother Scholl in which she writes that she is convinced that her children acted with a clear conscience. What had happened, she saw as God’s will.”

This article was published previously in the Dutch Reformatorisch Dagblad on May 8th 2021.